ONE OF THE LONGEST HIGHWAYS in the United States is Highway 50, which stretches from Ocean City, Maryland, to Sacramento, California, and passes through Washington D.C., Cincinnati, St. Louis, Kansas City, Carson City, Lake Tahoe, and Central Colorado. A sign at Ocean City declares this coast-to-coast highway is 3,073 miles long.

Before 1972 legislation shortened Highway 50, the highway went from Sacramento to San

Francisco by way of Stockton and Oakland. Yet despite this act of belittlement in

California, Highway 50 is still regarded as one of the last coast-to-coast highways that

remains intact -- since the road to San Francisco was merely replaced with Interstate

names.

(The highway is littered with places to stay for the night so you should have no

trouble being able to find hotels

in Chicago for example if your path takes you through there.)

Time Magazine (July 7, 1997) called Highway 50 "the backbone of America". But one could also call it "the backbone of Colorado" since it has had a major historic role in the development of our state.

The primitive beginnings of the Highway 50 route through Colorado began in 1821 with Captain William Becknell's Santa Fé Trail.

A debt-ridden Kentuckian -- no doubt influenced by stories of Zebulon Pike and a host of courageous mountain men -- Becknell left Missouri in '21 and headed west with a small pack train, and three companions. As luck would have it, the party made it to Santa Fé, where they garnered a generous profit on their trade goods.

Therefore, Becknell returned the next year with a much larger company. But on his second trip, he avoided the treacherous crossing of Raton pass he had endured on his first journey by swinging south out of Kansas and heading across the arid countryside toward the Cimarron River.

The Cimarron route proved so dry, however, that the men had to kill their dogs and drink water from the stomach of a buffalo and blood from the ears of their mules, just to survive. But once again, they made it.

And thus, two routes of the Santa Fé trail were founded. The mountain route went past

Bent's fort and over Raton Pass, and the Cimarron Route cut through northern New Mexico.

Before road improvements, however, the steep, narrow, brush-clogged paths up Raton could

be negotiated only if wagons were disassembled, carried over, and reassembled on the other

side. So in spite of its treacherous nature, the Cimarron Cutoff was often favored over

the Mountain Branch during the early days of the Santa Fé trade.

(These days with the route being so long you could book a stay in any San

Francisco hotels and be out on the west coast in a few days depending on

your driving.)

Today, Highway 50 basically follows Becknell's mountain route from Independence,

Missouri, to present-day La Junta.

In the 1830s and '40s, thousands of traders ferried millions of dollars worth of goods over the Santa Fé Trail. Then in 1846 and '47 the Mexican War brought not only an increase in usage, but a new government interest in the trail. By 1852, the Santa Fé Trail had a branch that run up the Arkansas River toward the future townsite of Cañon City.

Originally created for the purpose of reaching the trapping stations along the Arkansas River, that branch acquired an outpost in 1859, when Cañon City was established as a supply town for those heading into the mountains seeking gold.

In 1860, the future route of Highway 50 was once again extended (but not yet followed), when entrepreneur Joseph Lamb started a pack train of ten burros to carry goods from Cañon City to the placer mines of the Upper Arkansas Valley. Since no roads existed, Lamb had to follow old Indian trails up Copper Gulch and down Texas Creek and then up the Arkansas River. In some places along this route, he had to fight his way through heavy brush.

Finally, in 1874, a wagon road was officially built on Lamb's Copper Gulch route, and that same year stagecoaches began running between Cañon City and the agricultural community called Centerville (in the present-day Mesa Antero area).

Stagecoaches did not run past Granite, however, until the silver rush to Leadville in 1877. Like a virus, though, the Leadville rush led prospectors to search for silver elsewhere. On what was then known as Limestone Mountain (renamed Monarch Hill), Nicholas C. Creede (for whom Creede, Colorado, is named) discovered silver in what he called the Monarch and Little Charm claims.

Creede welcomed the Boone brothers (Hugh and Sam) as partners in his mining venture. The Boone brothers are said to have later constructed the Monarch Pass Toll Road in 1880. By May 1881, a stagecoach could also cross the pass to the Tomichi and White Pine mining camps in the Gunnison Country.

THE COMING OF THE RAILROAD to the Upper Arkansas Valley in 1880, however, would eventually spell the end to the stagecoach era. But by 1900 the automobile era had begun in Colorado, and automobiles brought a renewed interest in road construction.

In 1905, Col. W.H. Moore of the National Good Roads Association offered to come to Colorado to assist in holding a good roads convention if the sum of $750 was sent to him in St. Louis. Money for Moore was raised through the Denver Chamber of Commerce, and Governor Jesse F. McDonald issued the call for a state convention to be held in Denver in July of 1905.

Each city and county was asked to send accredited delegates, and sixty-five delegates attended this inception of an organized lobbying effort for "highways" in Colorado.

Although people with wagons would have benefited from better roads, there was a widely held belief that the good roads movement would benefit only people who could afford automobiles. Therefore, the good roads movement did not secure a bill for the creation of a state highway commission until 1909.

At a meeting in February 1911 at the Elks' Hall in Salida, all the prominent men in road building, including the well-known Otto Mears, were reported to have been present to examine plans for a proposed "Rainbow Route" highway between Pueblo and Montrose that was to be a continuation of the old Santa Fé Trail.

In 1883, Otto Mears had constructed a road in the San Juans called the "Rainbow Route" between Ouray and Silverton, but in 1926 this Red Mountain Pass road had become the first section of the Million Dollar Highway to Durango. Although the newspaper never said it, the Montrose to Pueblo road might have been named in honor of Otto Mears's famous San Juan road. The Salida Record, however, reported that the visitors were treated at the Monte Cristo Hotel to "delicious rainbow trout for which the highway has been named."

All present at that 1911 meeting promised their support of a bill that would ask for the appropriation of $50,000 to assist in building this new Rainbow Highway. And in April of 1913, the county commissioners of Montrose, Hinsdale, Chaffee, Gunnison, and Frémont counties received $88,000 in state funds to build "the Rainbow Route."

But the task of finishing the road in the canyon between Salida and Cañon City and extending it on over Monarch Pass presented some big and expensive problems.

On Monarch Pass the existing wagon road had to be straightened and widened to help eliminate dangerous curves, especially between Garfield and Monarch. Though the 1880 Monarch Pass went through the area now occupied by Monarch Ski & Snowboard Resort, it was decided that a new, shorter route to Gunnison should be located.

Likewise, the existing wagon road between Salida and Cañon City still went up Copper Gulch to Road Gulch and on to Cotopaxi. Thus, a shorter route was sought through what the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad called "the Grand Cañon of the Arkansas" (officially renamed Bighorn Sheep Canyon in May 1990).

Naturally the creation of shorter routes ended up costing much more than the appropriated $88,000 in state funds.

The work on the Salida-Cañon City cutoff started in July 1913 and was completed in September 1915 with a celebration and dedication at the convict construction camp at Echo (18 miles west of Cañon City). The canyon highway ended up costing Frémont County about $50,000 and the state $100,000. The cut-off was 21 miles long, which was 11 miles shorter than the Copper Gulch road. Ten miles of the road was built with free labor, and the rest was built with convict labor.

Work for a new route over Monarch Pass did not begin until July 1919. During this highway work, a campground complete with ovens and shelter houses was built at Monarch Park in 1920, and the new Monarch Pass was opened for auto travel in September 1921 with a celebration and dedication at Monarch Park. This 22-mile road was reported to cost about $10,000 per mile. The 1919 pathway taken over the Divide is today known as Old Monarch Pass, a pleasant gravel road in the summer and a favorite cross-country ski route in the winter. The 1880 route is called Old Old Monarch Pass.

ON THE WESTERN SLOPE, Gunnison and Montrose counties imposed a tax costing four dollars per person to help pay for their part of the "Rainbow Route." The people of Montrose and Gunnison counties even built a rest stop, west of Blue Mesa, known as the Halfway House. This large 22'x66' log house had three large rooms on the main floor and was said to have had several bedrooms above. The one and a half story house was dedicated on October 19, 1915, with several people from both counties present as well as several photographers from the press. People came to the celebration on horse back, buggies, wagons, and in autos. The dedication included food, games, and several speakers just as did the celebrations at Monarch Park and Echo.

Besides cooperation between counties in building highways, cooperation between states was also needed in building highways. On July 11, 1916 the Congress of the United States passed the Federal-Aid Road Act, which served to promote the improvement of an interstate system of through roads so that a traveler's progress would not be impeded by a state's reluctance to improve its roads.

But it soon became necessary for the United States Congress to get further involved in highway building. Thus, in 1925, Congress passed a bill calling for the creation of uniform danger and informational signs to help speed the interstate tourist on his way.

Motoring along the Grand Cañon of the Arkansas (now called the Bighorn Sheep Canyon) in the early days of US 50.

This also meant that interstate connecting highways had to have the same number. Therefore, a committee of federal and state officials signed an agreement at Pinehurst, North Carolina, on November 11, 1926 that designated names for all federal highways in all 48 states. Highways going east to west were given even numbers and highways going north and south were given odd numbers. Major coast-to-coast highways were assigned numbers ending with zero.

IN MARCH 1931, the state highway commissioners of Kansas announced their plan to inaugurate a hard-surfaced Highway 50 through their state to connect the Santa Fé Trail at the Colorado-Kansas state line. They called on Colorado to likewise establish Highway 50 in their state. And in June the Highway 50 Association was organized in Salida.

Composed of representatives of civic organizations in Montrose, Gunnison, Delta, Saguache, and Chaffee counties, and their respective county commissioners, the association's principal purpose was to see to it that Highway 50 received a standard hard-oiled surface. It was decided that two obstacles to a good highway lay in their way -- the lack of a good route through the Royal Gorge area and the lack of a non-torturous route across the Continental Divide.

Looks like a nice day for a ride, sometime in the 1920s, on US 50 as it passes the Hutchinson Ranch between Salida and Poncha Springs.

A minor rerouting of Highway 50 took place in December 1934 when the city council of Salida succeeded in getting Highway 50 routed through downtown Salida, which already had been paved in June 1930. At this time, the old Rainbow Route followed the river through the old townsite of Cleora before connecting to the road to Poncha Springs. That route did not veer off from following the river through Cleora to cut across pasture land as it does now to connect to the Poncha bound road. Highway crews made changes in the signs to direct traffic along East First to F Street. Highway 50 traffic then went up F Street to the Poncha-bound road. This route was used for about 20 years.

The erection of a four-way stop sign at the corner of First and F streets eventually became the site of many accidents and traffic snarls. So a traffic light was placed at this intersection in June of 1949. Despite the traffic light, though, the present Highway 50 route that bypasses downtown took shape with some protest by downtown merchants.

Highway 50's reconstruction and oiling for a hard smooth surface began in 1935. The highway through Pleasant Valley had paralleled the railroad through the towns of Cotopaxi and Howard on the north side of the river. The new highway route was constructed south of the river (possibly during the summer of 1935). Eventually businesses for these towns made a move across the river.

THE ROAD BETWEEN Parkdale and Texas Creek was closed the entire winter of 1936-37 by construction work. Many of the curves were removed and many of the highway grades were reduced to help make the highway more pleasant to travel. Some oiling and re-oiling was done during the summer of 1937. During the winter of 1937-38 a $300,000 overpass was constructed at Parkdale so that the highway would no longer cross railroad tracks there at grade. The construction of the Salida-Cañon City road was completed by the end of March 1938.

As for the rerouting of Monarch Pass, three plans were being examined in the 1930s. The plan that the city council of Salida and the Highway 50 Association supported was for Highway 50 to go over Marshall Pass (elevation 10,846 feet and then also the route of the narrow-gauge rail line). The argument was that it was lower in elevation than Monarch (11,375), and thus received less snow. Monarch Pass was closed for most of the winter, and it was thought Marshall Pass could stay open all winter. A highway, it was argued, built on Marshall would have the added advantage of not having to cross the railroad switchbacks that were on the eastern slope of Monarch Pass, part of the spur line that served the limestone quarry.

THE PLAN THAT SALIDA'S city council was most opposed to was for Highway 50 to take off at Coaldale and go over Hayden (10,780) and Cochetopa (10,067) passes, thus bypassing Salida. Truckers seemed to be the only ones in favor of the Hayden-Cochetopa Pass plan. Both Hayden and Cochetopa passes were lower than Marshall and an improved Hayden Pass would be shorter than the truckers usual Poncha-Cochetopa route.

The plan that was chosen by State Engineer Charles D. Vail in September 1938 was to have the highway take a somewhat detoured Monarch Pass route over what was being called Monarch-Agate Pass (11,312). The plan was to build this new highway with no grades in excess of six percent and to have no curves more than 16 degrees. Much of the new pass would be located high up on the sunny slopes of the mountains to aid in keeping the pass open year round. Surveys showed this route would be 1.8 miles shorter than Marshall Pass.

The Monarch-Agate Pass road was built with some protest from citizens on the eastern slope of the pass. The highway engineers had decided that the highway had to be built above the towns of Arbourville and Garfield to catch more of the sun's rays. This meant the highway had to be built over and through their cemeteries.

Frank Gimlett, a former proprietor of the Salida Opera House and writer of a series of paperback books called Over The Trails Of Yesterday, was greatly disturbed about the highway department's decision. He claimed in one of his books (Book Six) that the highway department with "fiendish glee" dug up and crushed the bones of departed pioneers in the middle of the night. The highway department, Gimlett claimed, did not want to bother with careful removal and relocation of the cemeteries. Gimlett proclaimed the Monarch-Agate Pass highway to be "The Ghost Highway Of The Rockies."

Except for the paving, the Monarch-Agate Pass road was completed in November 1939. Just before the pass was completed, there was talk about renaming the pass after highway engineer Vail. Area residents protested renaming the pass "Vail Pass," and some Vail Pass signs erected by the highway department were either torn down or painted over. Governor Ralph Carr in early December 1939 officially designated the new Highway 50 pass "Monarch Pass." About a day or two after Carr's proclamation, Eagle County demanded that a pass there be named "Vail Pass."

IN CONJUNCTION WITH the building of the new Monarch Pass, a ski area was created at the Continental Divide crossing of the original Monarch Pass. The ski area was constructed by the city of Salida under the Works Project Administration (WPA), a President Franklin Roosevelt unemployment program. The construction of the ski course was completed in December 1939, and the Monarch Winter Sports Area was dedicated in February 1940. The new Monarch Pass was oiled in the summer of 1940, and it was decided in April 1941 that Old Monarch Pass would be kept open in the summer for tourists.

In January 1948, two Colorado organizations that were promoting Highway 50 merged into one group called the Colorado Highway 50 Association with Pueblo being the central point. The organization was divided into two sections, one east of Pueblo and one west. The group proposed to publicize the highway with the theme "On the romance trail through the treasure chest of the west."

Parts of the highway continued to be rerouted and reconstructed to try and make Highway 50 the main road through Colorado and not just a side road. A new route was constructed east of Cañon City to shorten the distance between Cañon City and Pueblo by nearly seven miles. The new route was also made to feed into the Colorado Springs highway and lessen that route by two miles. Hazardous and time-consuming curves were eliminated and the new highway bypassed both Florence and Portland. The new highway involved the construction of three new bridges: Four Mile Creek, Six Mile Creek, and Beaver Creek.

CAÑON CITY'S SECTION of Highway 50 ran along Main Street until the 1950s, when the highway department decided to move traffic to a parallel street one block south -- River Street, which is now a four-lane thoroughfare called Royal Gorge Boulevard. Gradually many of the houses along Royal Gorge Boulevard were torn down for the erection of businesses along the new highway route.

Salida's Highway 50 downtown route was also bypassed. But in May 1955, the downtown merchants succeeded in getting Highway 50 divided with signs giving travelers a choice of taking the Poncha route or the inter-city business route. Seven parking meters were removed to aid visibility at the F and First Street intersection. It is unknown when or why signs for a choice of Highway 50 routes were removed, and replaced with just a downtown area direction sign.

In June 1957 Mark U. Waltrous, chief engineer of the Colorado State Highway Department, told 34 members of the Colorado Highway 50 Association that Highway 50 "is the best route over the Continental Divide." He talked at the annual meeting in Salida telling the Association's members of plans for future improvements that included three-laning the highway at the Parkdale Hill, west of Cañon City, and three-laning sections of Monarch Pass.

In July 1968, a "safety" $250,000 project took place on top of Monarch Pass that involved the creation of five lanes of traffic as well as parking lanes on both sides of the highway for trucks. Fill created by the cutting away of the embankment for the .4 mile highway expansion was used to double the size of the Monarch Crest parking lot. Although the turn and entry lanes made turning into the Monarch Crest parking lot safer for tourists, the numerous lanes caused some confusion as to which lane was a parking lane, turn lane, or traffic lane. Large billboard-size signs were then erected explaining which lane was for what.

Another highway five-lane widening project occurred on Salida's Rainbow Boulevard during the summer of 1973 to aid travelers and shoppers in going on and off the highway. During the summer of 1974, the five-lane widening project extended between Salida and Poncha Springs.

![]()

FUTURE PLANS for Highway 50 include four-laning the highway from Pueblo to the Kansas state line. This long-term construction plan will take several years in designing and in right-of-way acquisitions. The reason given for the widening project is to make it safer for travelers to pass slow-moving farm equipment.

The Colorado Highway 50 Association basically disbanded in the 1970s, because they saw that tourists preferred to travel the "safer" divided four-lane Interstates that by-pass small towns. The national U.S. 50 Federation is said to still exist in the Federation's president, Doyle Davidson of La Junta. Another Highway 50 promoter is Wulf Berg who maintains a website at http://www.route50.com. His book is available at the Salida Regional Library. One can also find references on the web to Highway 50 as "the backbone of America."

Alvin Edlund, Jr., grew up in Salida, went off to Alamosa for a degree in journalism, and now works at the Salida Regional Library.

www.cozine.com

http://cozine.com/1999-january/how-us-50-came-to-pass-through-central-colorado

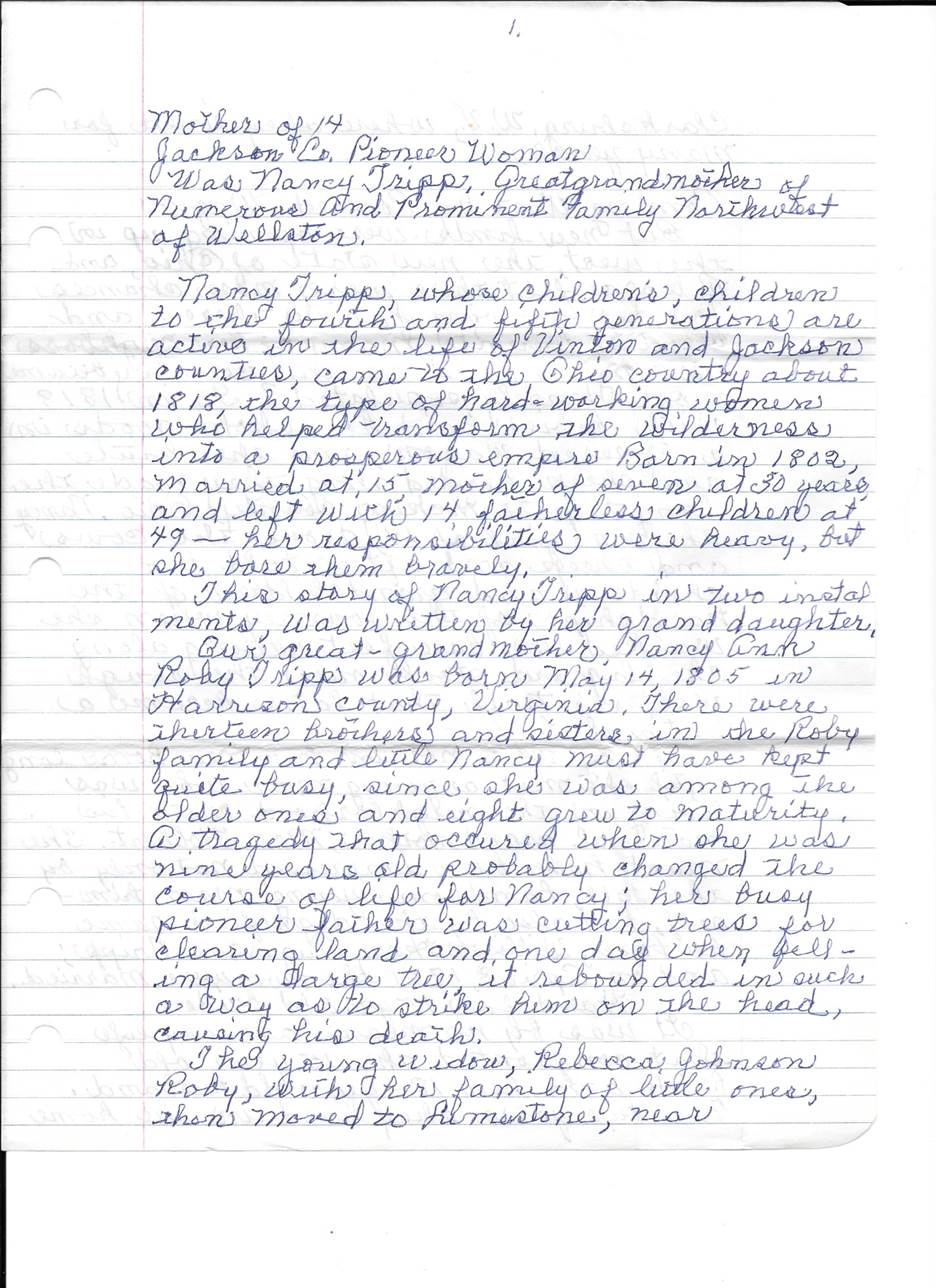

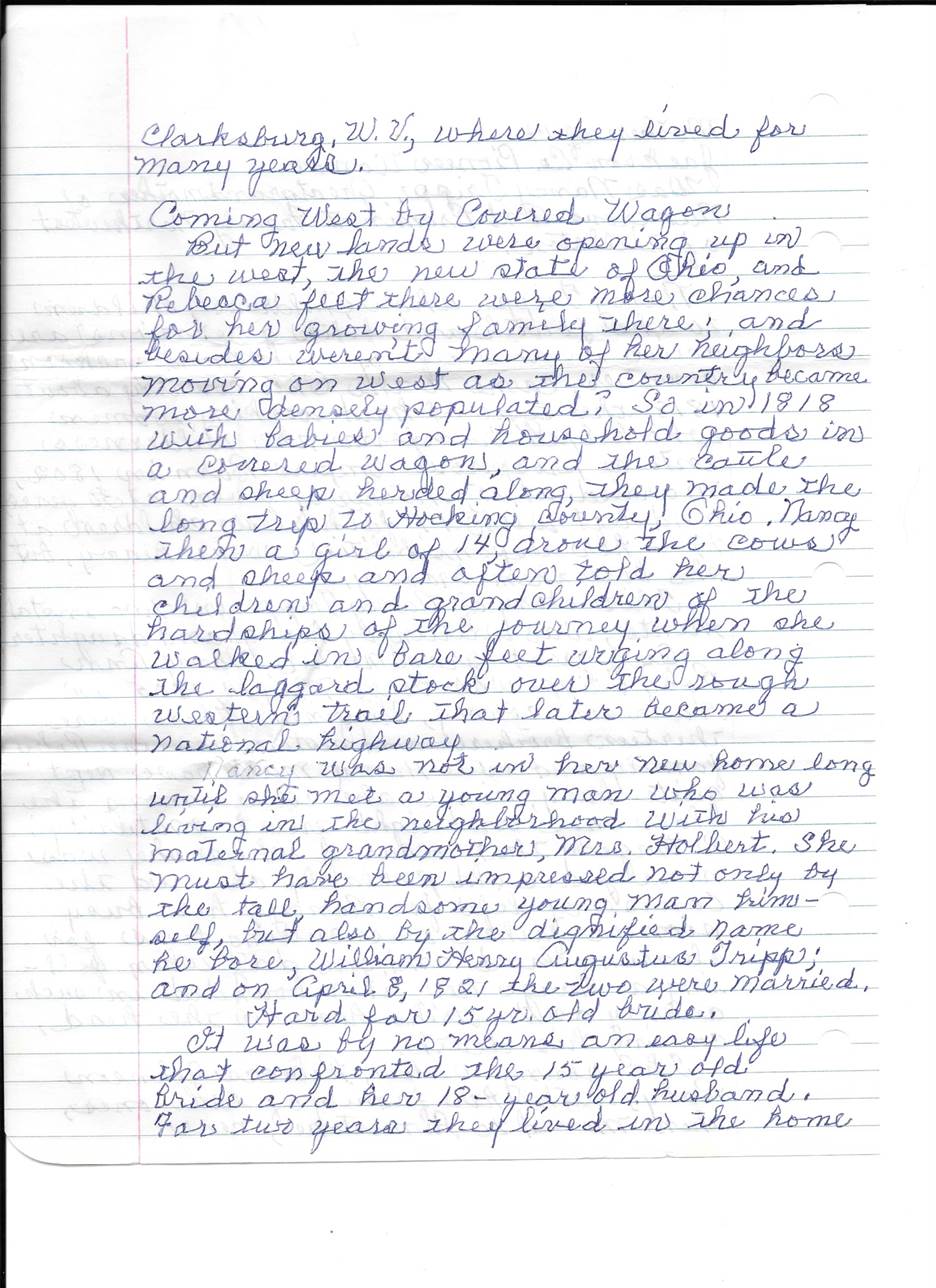

Hardship and Survival

Sixty miles southwest of Gunnison CO is the town of Lake City. One of the early explorers was a man named Alferd Packer. He lead a group of five would be miners to the Lake City area. Winter snow trapped them. Packer survived by eating his companions. Later the University of Colorado named their Student Union Cafeteria after Alferd Packer.

Elwood J Ensor <EJENSOR@prodigy.net >

From: Jennie Lyon Ravary,

My 5th Great Grandmother,

Rebecca Johnson Roby and her 14 children traveled from Limestone, Virgina, now

WV, through Clarksburg, to Hocking County. Rebecca was a widow, her

husband, Patrick Moreland Roby, died when a tree he was cutting down fell on

him.

My 4th great aunt described to her granddaughter what the journey was like in 1818. They were traveling along the western trail that was to become Route 50, on their way to Hocking County, Ohio. They settled in Falls & Green townships.

Until 1979, Maryland Route 213 was U.S. Route 213, starting at U.S. 40 and running south (the part from U.S. 40 to Pennsylvania was Maryland Route 280). Prior to 1949, US 213 continued past Wye Mills all the way to Ocean City, junctioning its parent US 13 in downtown Salisbury. The route was truncated when U.S. Route 50 arrived on the Eastern Shore due to the impending completion of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge, and as a result US 213 no longer crossed US 13. he Bay Bridge opened in 1952.

Highway 50 & Lincoln Highway

Highway 50 and the Lincoln Highway share history from Ely, Nevada to San Francisco, California. Today US 50 ends in Sacramento. To trace prior routing one must follow the Lincoln Highway route in California from Sacramento to San Francisco. "The original 1913 route followed what is now Highway 99 south to Stockton. From there, I-205 and I-580 now parallel much the same route the Lincoln Highway took into Oakland. A ferry once crossed the bay from here to San Francisco. For more detail on the route from Tracy to Oakland, see this Oakland Tribune article and map." (Lincoln Highway Assoc.)

Norman Ramos provided the following routing for US 50 from 1934 to 1949. "Highway 50 started in San Francisco and came across the Bay Bridge, out Moss Ave, and Foothill Blvd. through a short section of a realignment called 'Hollywood Blvd' built in 1935 - 36, then on Foothill again through San Leandro, Castro Valley, Dublin, Livermore, Tracy and Stockton to Sacramento".Leon Horst informed us that "the Alameda County Assessors Index Map still identifies Interstate 580 as U.S. Highway 50."

"In San Francisco, the Lincoln Highway ran from the Ferry Building along Market Street, turned west on Geary Street, then right on 34th Ave., which becomes Legion of Honor Drive. The western terminus of the Lincoln Highway is at the Palace of the Legion of Honor in Lincoln Park." (Lincoln Highway Assoc.)

Sacramento to South Lake Tahoe

I live just off of Hwy. 50 to the north, about 1 mile in north east Camino, CA. 95709 at 3080 feet elevation on a hill top. I have lived here since 1975 at what is called Snow line (it's snowing today, about 4" so far). There are hand hewn Granite markers now mounted on the south side of "Pony Express Trail", "Old Hwy. 50" the new Hwy. 50 alignment was made in 1959 - 60 when the freeway was built. The Granite markers are mile markers going east from Placerville to Pollock Pines, which is at mile marker 13. These markers stemmed from earlier days when the Stage Coaches came down from Nevada and South Lake Tahoe to Placerville, thence to Folsom and Sacramento. A History Guard at Folsom Prison told Public Television that the Highway 50 Mile were hewn and carved by the prisoners at Folsom to be placed along the right of way of the 1930's route, from Placerville to South Lake Tahoe. A few still exist on Pony Express Trail, from Camino to Pollack Pines (i.e. 8 mile, 12 mile and 13 mile which is in Pollock Pines). From 1964 to 1969 I worked on the "Eldorado National Forest" as a Forest Road Designer and Surveyor. Hwy. 50 goes right through the middle of the National Forest. I designed many of the recreational and logging roads in the higher elevations.

Norman Ramos ramosna@directcon.net

The B&O Railroad came to Grafton, WV.

The B&O line went from Grafton WV to Wheeling in the 1840s. The Cincinnati and Marietta was built in the late 1850s. The B&O built a line from Grafton to Parkersburg and in 1874. A bridge was built between Parkersburg and Belpre, OH. The B&O then built a line from Belpre to just east of Athens. The B&O already controlled the C&M and in 1875 - 1876 the line from Caananville to Kilvert OH was abandoned. The rest of the line to Marietta was taken over by coal hauling short lines. The CSX abandoned the line between Clarksburg and Cincinnati in the late 1980s or early 1990s.

Bob Gillis rpgillis@bellatlantic.net

Route 50 and Pershing Drive at Fort Myer

On September 9, 1908, near this site, Orville Wright carried aloft in public his first passenger, Lt. Frank P. Lahm, for a flight lasting 6 minutes and 24 seconds. Three days later, he took Major George O. Squier on a flight of 9 minutes and 6 seconds duration. From this primitive beginning has evolved an air transportation system that today spans the globe.

Route 50, at entrance to Fort Myer

The first heavier-than-air flight in Virginia was made by Orville Wright at Fort Myers [sic.] on 4 September 1908. A United States Signal Corps log noted the flight spanned three miles at a height of 40 feet. The engine's condition following the flight of four minutes and fifteen seconds was described as "good." The engine ran a total of six minutes.

Old Barn

on Route 50

between Fairfax and Middletown, Virginia

Richard Elliott, 29 Sep 1985

A rainy cold afternoon in December brought us to Gilbert's Corner, Virginia a place we had visited many years ago. We, like many others of our day, would take auto rides during the weekend particularly on Sunday afternoon and drive through the horse country of Northern Virginia to see the magnificent horses, old barns, green pastures and the old, old trees with twisted and odd shaped limbs reaching for the clear blue sky.

So today was special in that here we were at Gilbert's Corner and it brought back old memories of previous pleasant trips. As we turned right onto US 50 from Highway 15, the day was overcast, wind from the North with a heavy rain falling, but our spirits were high and we had high hopes of seeing again the Old Barn that I had drawn so many years ago when we lived in Fairfax City.

We drove east looking for the Old Barn which I remembered was on the south side of Route 50. We drove and drove passing several new housing areas with fancy sounding country names and all the time thinking that the Old Barn had been destroyed and replaced by a group of new houses.

Many of the areas are very attractive and up scale with great front entrances and it struck me that Route 50 in this particular section had changed a great deal. One could see every now and then an old familiar building that seemed to say, "I've been here before those new houses, but you don't recognize me?" Many I did recall, but its been years since our last outing along this highway.

We continued on and when we could see what we thought was Chantilly in the distance we decided to turn around and retrace our trip back to Gilbert's Corner and Highway 15 for we were going to our daughter's home for a family dinner on Christmas Day.

Well, as we turned back west there was the Old Barn about 100 to 150 yards tucked back behind a row of pine trees growing along the road's shoulder and blocking our view when traveling East.

This section of Highway 50 (John Mosby Highway) is dual lane so when we turned around we were much further from the barn than when I originally drew it, 25 or so years ago. At that time the highway was only two lanes and very quiet. The weather was so bad it was not possible to get a photo, but I noticed that some of the roof is missing and time has done it's thing to the Old Barn which is located on the Southeast corner at the intersection of Highway 50 and Route 639. It is 8.2 miles East of Gilbert's Corner.

I don't know of any historical data concerning this Old Barn, but it attracted my attention many years ago and to this day represents a time gone by on Highway 50. All things change for that's the way of life on earth and Highway 50 is no exception, but it was a thrill to renew old memories and sight's of a much beloved National Road that stretches directly across the middle of our great country -- like a barometer -- judging our strengths and weaknesses and of course our changes.

Richard L. Elliott, December 24, 2004

The Highwayman's Road Reports

Joel Windmiller. , known as the Highwayman has supplied the following information:

| Alternate

US 50 is a route used when US 50 is closed due to fire or weather related conditions.

Alternate US 50 goes from US 50 at Pollock Pines to SR-88 at Iron Mountain Road. Continues

with SR-88 to Picketts Junction turn left on SR-89 into Lake Tahoe. US 50 once went from the US 40-101 junction in San Francisco to Stockton US 99 to Sacramento. Then turned east into the Sierra Nevada to Lake Tahoe. US 50 from Oakland to Tracy was once US 48. After the decommissioning of US 48 in the 30's |

Hi Folks,

here is some first hand history on Highway 50 not found on your site.

Hamilton County, Kansas History

US-50 enters Hamilton County at Milepost 48 and exits into Colorado at Milepost zero. Upon entry at its eastern edge, the visitor will be introduced to the Mountain Time Zone. For many years, Mountain and Central Time took up land in several counties in Kansas, but through the voting booth, the Mountain Time Zone has been reduced to four. The visitor has also been traveling along the Arkansas River for the past 50 miles or so and will travel along the River route through the county. The River is one or two miles from the highway for its length of Hamilton County and is a source of recreation for the locals who fish, swim, and ride stock tanks down its waters.

Kendall, Kansas is at the eastern edge of Hamilton County's border along the US-50 route. In the early days of the county, the border was extended several miles into Kearny County to the east and the town of Hartman was on the eastern edge of the County. Kendall and Syracuse entered into a war to determine which town would be the seat of Hamilton County, with records stolen and mayhem. Syracuse won and Kendall died out. Now, it is part of an organized township of less than 100 people with a water system, a few houses, grain elevator, a couple of businesses an post office, and not much more.

Somewhere along the route in Hamilton County was the site of Ft. Aubrey, a trading post that lasted for a year or so. Also, Syracuse, 10 miles into the county, is the county seat with about 1,700 population and various businesses including the historic Northrup Theater, a museum, bowling alley, new swimming pool, and a city/county airport, to name a few.

Seventeen miles further west is the City of Coolidge, population around 90 people. At one time, Coolidge had around 3,000 residents. The railroad ended the cattle drive days and Coolidge is now a shadow of its former self.

Among the ghost towns of Mayline and Medway, which no longer exist, was the town of Trail City. Located in both Kansas and Colorado, Trail City's claim to fame was a bar that was surveyed with its east side in Kansas and its west side into Colorado. If you got into trouble on either side and jumped over the line, the Marshal on that side could not follow you into the other. There used to be some foundations left, but they no longer exist.

Mike Keating

Emeritus Sheriff of Hamilton County.

US

50 -- Memories from the Past

US

50 -- Memories from the Past